Even into the 21st Century, advocates of Mary Surratt keep hoping that evidence will surface proving her final words on the gallows to be true: "I am innocent."

But those hoping for her exoneration will be disappointed by Kate Clifford Larson’s book, Assassin’s Accomplice. Larson, initially setting out to prove Surratt’s innocence, became more convinced of her complicity in the course of researching the book. Though wisely leaving the bigger questions unanswered, Larson’s overall pronouncement is – guilty as charged.

I guess it is hard to believe that you could host a series of meetings at your boardinghouse and never once wonder what your son and his handsome friend were up to.

Larson unearths some careful evidence to back up her claims, but never loses that curious respect that we all seem to acquire for Mary Surratt. She points out that Surratt was one of the 19th Century’s true feminists. She embraced Catholicism against her family’s wishes, survived an abusive marriage to an alcoholic husband, raised her children virtually alone, ran her own business, became totally sold out to the Confederate cause, took a man’s risk in a dangerous adventure and accepted a man’s punishment for it. Like Belle Starr, she captures our imagination.

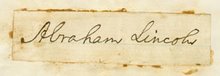

Interesting how Lincoln seemed to have trouble with women named Mary. But if her boardinghouse really was the nest that hatched the egg of the assassination plot, as Johnson claimed it was when refusing her pardon, then surely her death provided the first opportunity for a divided nation to agree on anything. Most people wanted her life spared and were surprised when it wasn’t – right up to the hangman who thought the rope he made for her would never be used.